When we think about truth in the corporate context, in business or in government, we are immediately thrown into a world where bureaucracy dictates, and ‘truth’ becomes a blurred construct.

But if you strip the word back and apply it in daily life – it’s a wonderful thing to think about – because truth at its purest is usually and often found with children.

We admire the beautiful naivety and blunt honesty of children. As parents, we can be embarrassed by the honesty of our kids, even mortified in certain situations – but the innocence of being honest and unaffected is bewildering.

It does make you wonder though, where and when does it all get lost?

When do we lose the ability to verbalise everything that comes to us without vetting it, without filtering? Perhaps we don’t lose it at all, but we’ve found a medium for it on social platforms where it’s disassociated from the innocence of truth and put into an active state of anarchism. Are we speaking our truth? Or just stirring the pot – becoming the antagonist in our own story?

The freedom to be ‘passively’ offensive – takes away the sting of offence – it’s all just honest inquiry when you’re 6 years young.

If you were to ask a psychologist, they could probably tell you exactly when ‘it’ happens. When in our subconscious mind, we forever change. Neuroscientists and paediatricians could probably tell you at what time ‘that’ part of the brain develops to shut off our instinctual responses and produce a more, socially acceptable version of ourselves. Despite what some people might say, babies and young children don’t know how to manipulate – they don’t guilt us by crying at all hours, they don’t refuse to crawl because they consciously want to stay reliant on their parents – they’re just communicating the only way they can.

Once we learn how to communicate effectively, we can protect ourselves and the feelings of others by not always speaking the truth. By hiding it. At some point in our youth, the way we communicate becomes a series of considered choices. We navigate life by deciding what to say, creating context, weighing up the advantages and disadvantages of speaking our truth. These are conscious decisions and we can only verbalise using the vocabulary we have available, so economic status can also come into play. But no matter your access to higher levels of education – It takes time to be learned – and to be cynical.

Our kids are learning about their surroundings now. About how they fit in and how people react to behaviour every minute. They’re little sponges, soaking up our atmosphere, absorbing all the things adults put out there in the world. Good or bad.

That’s why it’s so refreshing to hear children tell it exactly like it is, or at least, as it is in the world as they experience it.

Photo by Emre Kuzu

Photo by Emre Kuzu

Professor Uta Frith is a developmental psychologist who pioneered research into understanding autism and dyslexia. She talks about the mind as a garden – full of the most interesting, different things that have to be cultivated and constantly checked. ‘We learn by taking different perspectives – something about ourselves which we otherwise would never have known.’ (Uta Frith BBC Radio 4).

She has pioneered revelatory research into autism and has offered much commentary into the differences in how people’s minds work and how they interpret their worlds and the stimuli that surround them.

‘You do find that there is a different mind with different strengths and different weaknesses.’ Take what is given to you and make the best of it, but of course, cultivation is key to all of these things – so culture in our lives and learning, learning from other people. These are the really important things.’

But what can we learn when we listen to our little ones?

Beyond taking pleasure from their quirkiness and watching their characters develop – what can we hear when we truly listen? Taking note of what our kids say while they’re still blissfully ignorant, full of youthful naivety and energy is eye-opening.

We don’t often think about what even the smallest, and sometimes quietest members of our society have to say. They interpret the world based on what matters to them, based on what brings them joy. But we should think about it. Because we’re still learning too.

Understanding through language and culture

When we talk about the development of language over time, we can see just how much it’s changed over the last decade or so – perhaps more rapidly than ever before. Technology, a thirst for ‘snackable’ content or entertainment and the acronyms of the web made prevalent through mobile interactions (lol, wtf, rotfl) – are just some of the dictating factors that have led to the morphology of language as we’ve always perceived it.

Who would have thought words like the noun bae: boyfriend, girlfriend or romantic sexual partner, or the noun dorkus: a foolish, clumsy, or inept person, would as of June 2019, be etched into our vernacular in official terms — legitimised into the Oxford English Dictionary? Sophisticated entries? Perhaps not — but it’s worth bearing in mind that the next generation of writers, entrepreneurs, policy setters, politicians and teachers will be on familiar terms with these and many other words, still new and controversial to us. What stories will they have to tell? What will they be fighting for? and what words will win the hearts and minds of those they need to convince? (For a full list of new words you can visit the OED New Words List. )

Language is one very good reason for employing a range of groups within your organisation and embracing the differences within your teams. Collective knowledge that’s centralised and given context is powerful and transformative, as is a collaborative and inclusive company culture. By unifying all these differences, you speak to everyone!

The IRSA (International Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet) is often referred to as the NATO alphabet and has a few iterative variations depending on culture and geography.

The reason for the creation of a standard alphabet goes back to the first world war when the difference between what the Royal Navy used in comparison to what was used by the infantry caused confusion. Again, in the second world war, allied forces used yet another alphabet so US forces communicated differently to British, or Australian soldiers. It was the accents and word associations that caused the confusion – those cultural curiosities that are so endearing travelled with the individual and literally got lost in translation.

So why are we talking about phonetics, aviation and children in a knowledge management blog? Because truth and the disparate elements of communication that make us so evidently human in a world where AI-powered chatbots are speaking to us daily, are worth keeping hold of. They’re worth remembering when you’re implementing technology into your business. Having a system everyone can understand, that is streamlined and easy to navigate is essential to success – but don’t ever lose the cultural stamps underneath all of it. The human bit.

Humanising technology

The balance between utilising digital technology and people is not as difficult as it might appear. But it does require conscious effort and consideration.

Are you making the best of your technology platforms by maintaining the characteristics that matter to you? And are you appreciating every member of your team for the skills and attributes they bring to the table – like knowing that phonetic alphabet by heart and using it to communicate to your many customers far and wide – gathering information and solving problems? It’s easy to take these things for granted. Frith’s words about the different skills of each individual and the importance of cultivation, certainly resonate when talking about how best to share learning and grow a business — especially when so many different people, with so many different skills and ways of learning, all need to understand and share the same knowledge and technology.

Are you really listening?

Make sure you make the time to occasionally sit down with your teams and check in. Find out what matters to them, talk to them away from the screens and the phones – just like the Knosys parents have done with our little ones (the ones who can talk anyway) in this exercise.

It’s all about creating a balance, listening, appreciating and embracing the unique skills sets of each person and allowing technology to become a part of your company growth strategy – but not the whole story. Be credible without losing your character, be digitally transformative without losing the quizzical – and like all kids – never stop asking why?

The language of our little ones

If you’re interested in the truths and the joys of our under 10s, check out the phonetic alphabet according to:

Charlie, Will, Timmy, Charlotte, Alex and Allyssa. And if you’ve got a few moments to take away from your computers, mobiles, tablets and TV screens – we’d love to get some alphabets according to your little ones too – there are no wrong answers – just listen. And laugh, because that’s okay too. Here are some insights into the lives of little ones:

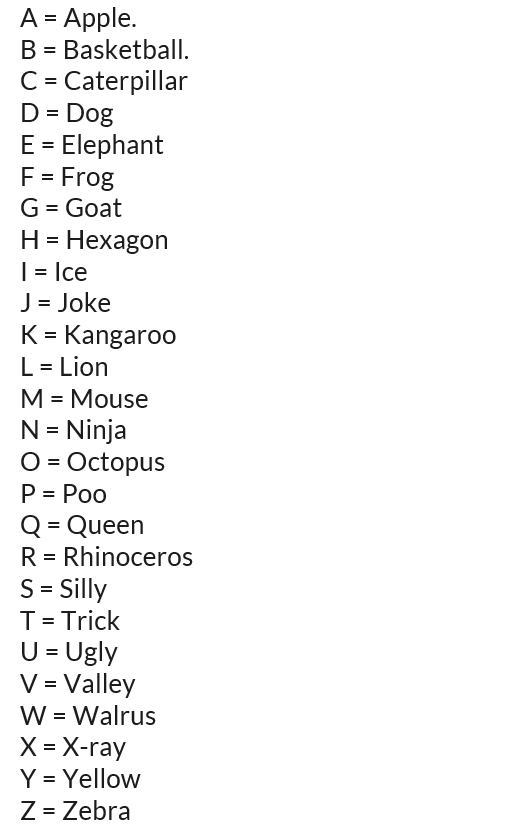

The phonetic alphabet according to Timmy – age 6

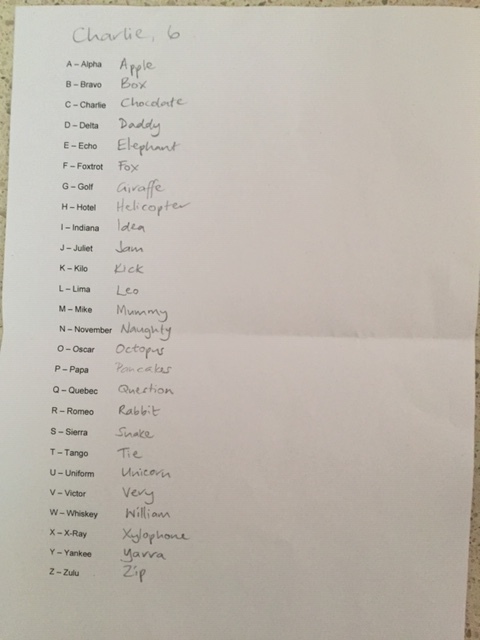

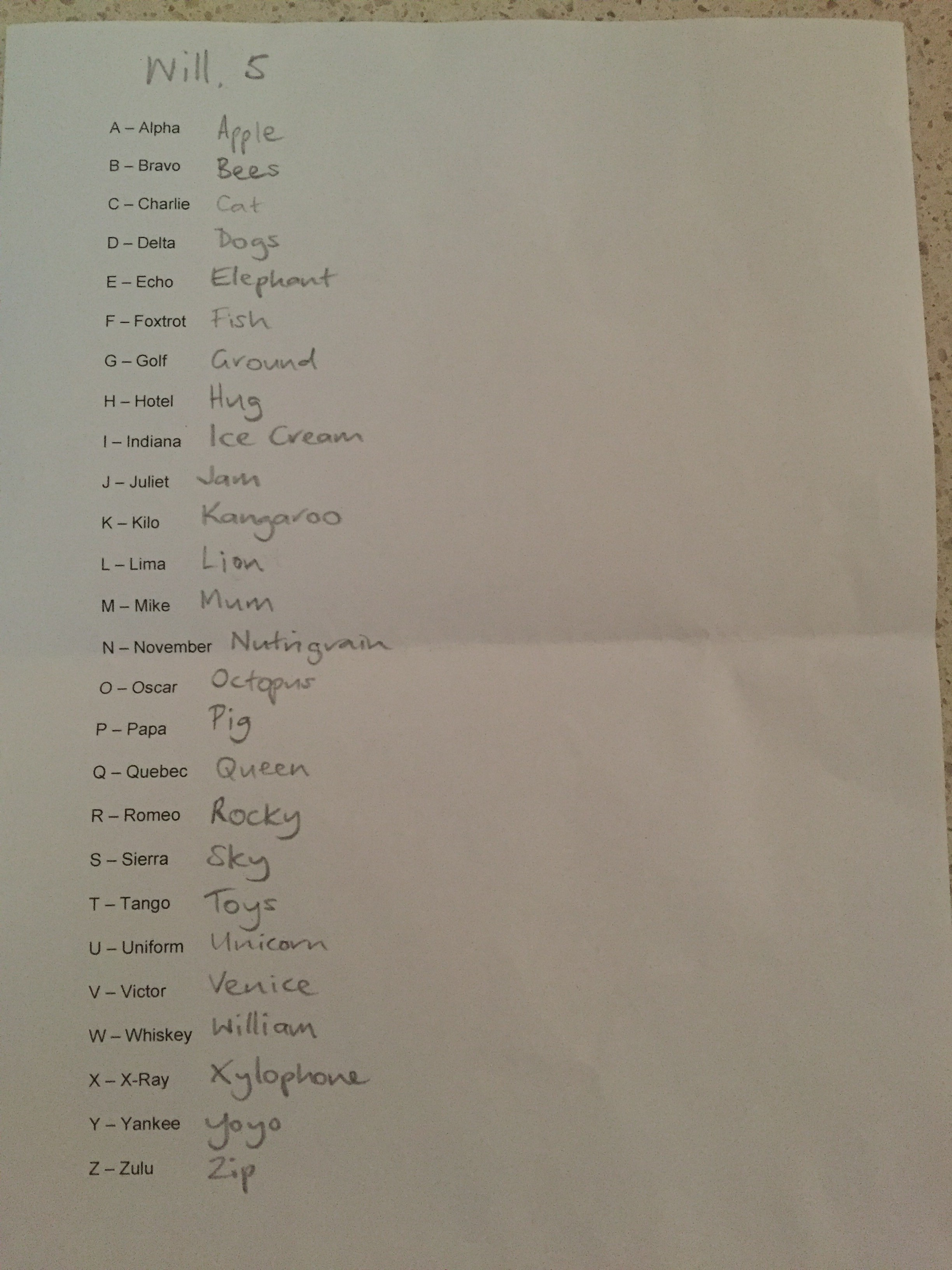

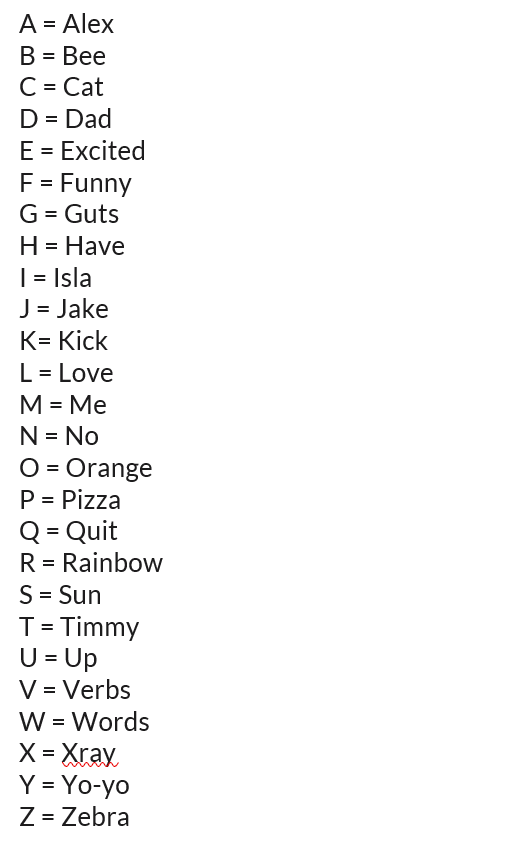

The phonetic alphabet according to Charlie aged 6 and her brother Will aged 5

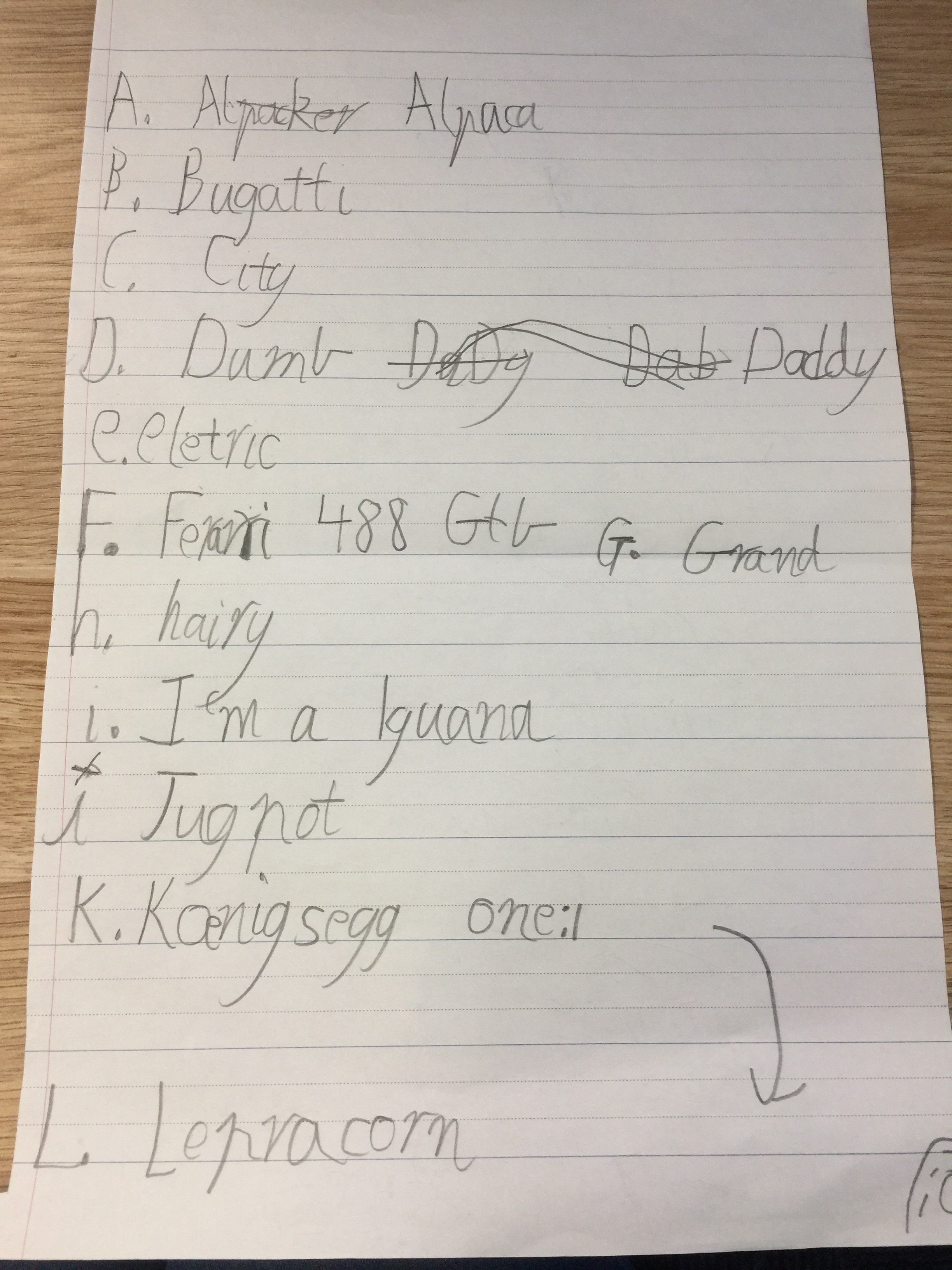

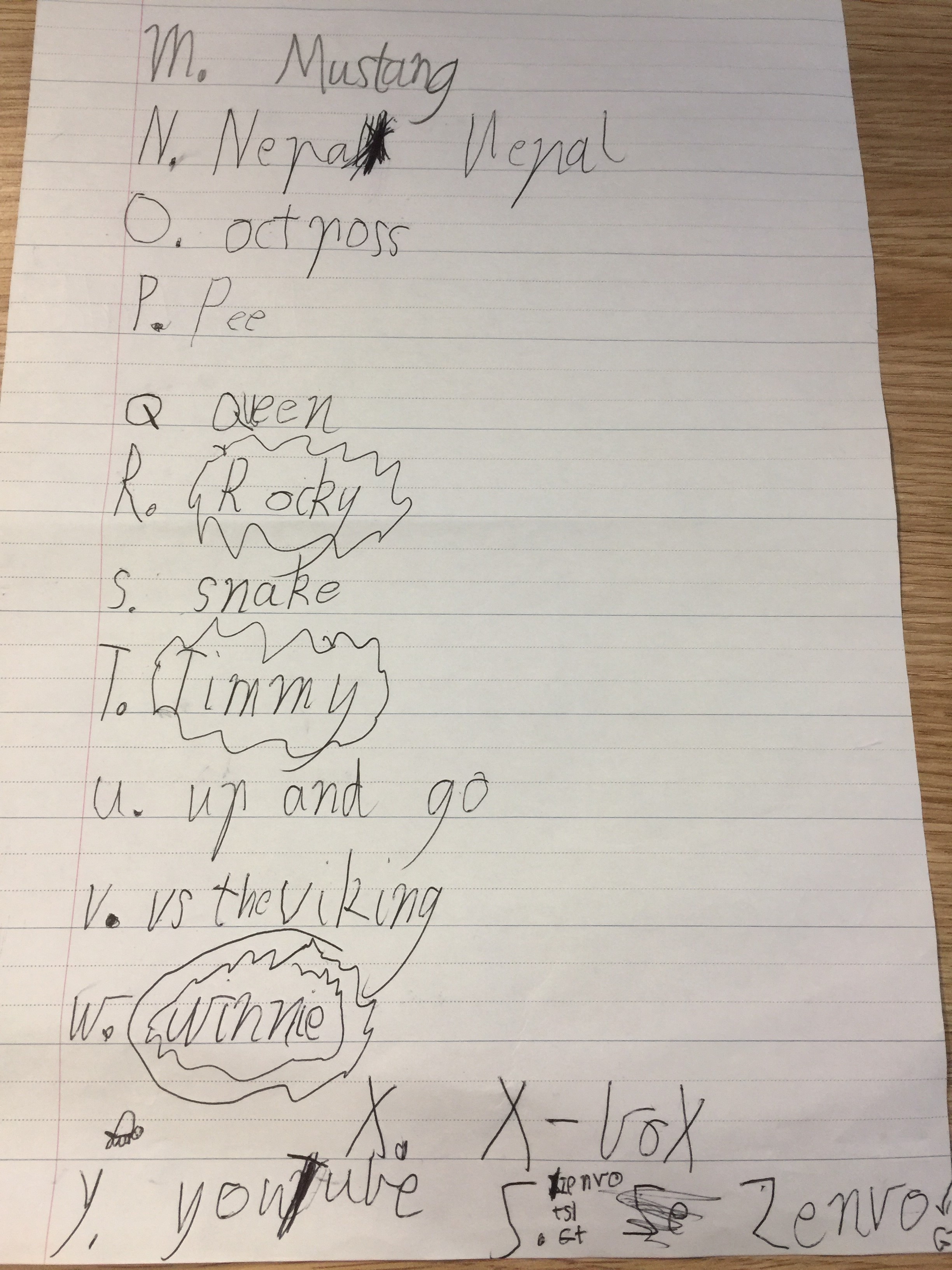

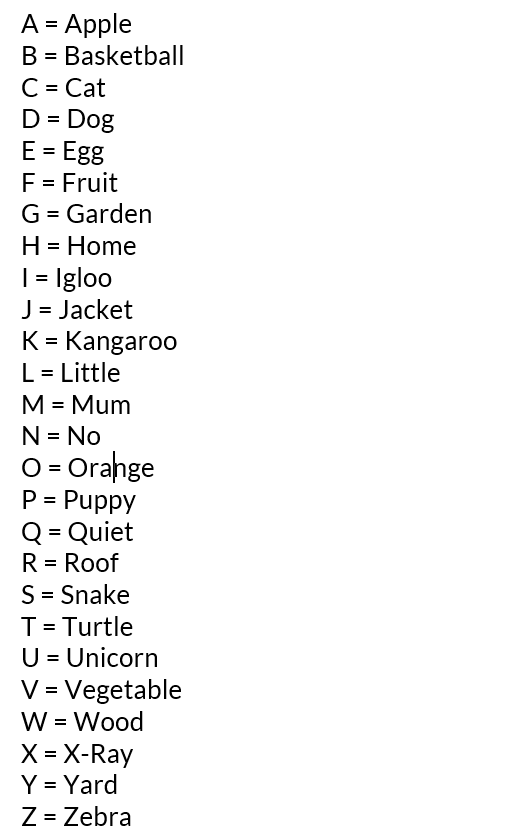

The phonetic alphabet according to Charlotte aged 8 and her brother Alex aged 6

The phonetic alphabet according to Allyssa aged 9

If you found this interesting you might like some of our other content:

{{cta(‘6dd001fa-7b7e-42aa-a3c8-7abdbd06b171’)}}